The management philosophy that underpins much of how we work today is Taylorism, named after the American engineer who developed the Principles of Scientific Management in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Despite having such a big influence on the world of work, very few people have heard of him.

Taylor is known as the Father of Scientific Management. He proposed that by optimising, simplifying, and automating jobs, productivity would increase. Taylor introduced an incredible range of then revolutionary management practices. Some may sound familiar, such as:

- the separation of decision making (managers decide, workers do);

- breaking tasks down and standardising them;

- time and motion studies;

- creating precise processes and procedures to follow to complete tasks;

- worker training;

- benchmarking and setting targets;

- best practices (what he called the ‘one best way’);

- forecasting and planning (working closely with Henry Gantt, creator of the Gantt chart);

- quality through inspection and checking;

- change by experts; and

- staff suggestion schemes.

Taylor focused on productivity and output and wasn’t concerned about worker motivation or job satisfaction. His belief was that all workers were inherently lazy and motivated by money, so he advocated the idea of ‘a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work’.

He was a mechanical engineer by trade, and this was reflected in his mechanistic approach to work – treating workers as machines or objects. He would time workers with a stopwatch, using the fittest and strongest man as a benchmark, and then expect other workers to achieve the same levels of productivity. If they didn’t achieve the targets, they lost pay or were replaced.

In the Industrial Age, Taylor became the world’s first management consultant.1 His Principles of Scientific Management were extremely popular, spreading around the globe. Throughout the 1900s, Taylorism grew to become the dominant approach to design and manage work.

You might be thinking it’s interesting to learn the root of these practices, but surely we have long since moved on from Taylorism. In today’s organisations, we have far more focus on the welfare of an employee; there are policies in place to ensure people are not treated like machines, and through the creation of Human Resources and People and Culture functions, employees are no longer subject to stultifying systems and structures.

Let’s examine whether this is indeed true – has Taylorism been relegated to history, or are his principles and practices still in use today? Three specific Taylor-based approaches have been chosen to test this hypothesis: process improvement, replacing workers with machines, and monitoring employees.

PROCESS IMPROVEMENT

In many organisations there have been many attempts to improve performance by using process improvement and/or ‘journey mapping’. Leaders start a process improvement initiative either through recognition that the organisation either has overly complicated existing labyrinthine processes or no formalised processes at all. The thinking is that employees will perform better when following clear processes. To create better processes, leaders often turn to process improvement specialists (what Taylor called ‘organisation and methods’ experts).

What ensues is the mapping of current steps involved in work and, just as in Taylor’s day, time-and-motion studies performed on each step, and attempts made to create simplified ‘target state’ processes. For large organisations with many divisions, business units, and functions, ‘process leaders’ are often employed and process frameworks adopted. Key ‘customer and employee journeys’ that stretch horizontally across an organisation are defined. The aim of all of this is to define clearly understood processes with a single point of accountability attached to each in the form of a senior manager (‘process leader’). As in Taylor’s day, each key process is treated as a separate production line. Each process aims to deliver standardised solutions that deliver the ‘optimal’ outcome.

Once created and digitised into workflow software, new processes are deployed, which employees are trained to use. The usage of the new ‘best practice’ processes is monitored for effectiveness, often involving further time-and-motion studies and technology, an example of classic Industrial Age thinking that wouldn’t have been out of place in the early 1900s.

Sadly, simply improving processes never works very well. New processes are put in place, but things don’t work as anticipated, so ‘workarounds’ are put in place (often involving technology), adding more steps into the process each time. This continues until such a point where someone comes up with an ‘idea’ to improve and simplify the processes again, and the cycle restarts. Repeated process improvement is undertaken, but it doesn’t improve anything in the long term.

We have seen organisations invest millions of dollars (sometimes hundreds of millions) on process improvement with little to no effect, but that has not stopped organisations from continuing down this path. Taylor’s practice of process improvement is certainly still a feature of the current workplace, but what about his drive to replace workers through mechanisation?

REPLACING WORKERS WITH MACHINES:

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (AI)

Once processes are in place, tools are often employed to further automate steps within the process to achieve additional efficiency and further reduce costs (i.e., no need for people to do them). In Taylor’s time, this was about adding physical tools, implements, and machines. Today, it is about automation through technology.

This thinking is becoming more prevalent with the advent of artificial intelligence and intelligent automation. Replacing ‘costly’ workers with robots to improve economic efficiency is a Taylorist dream. Taylor called his Principles of Scientific Management a mental revolution. The AI revolution, as it is called today, is here, and the race to employ AI is on.

It is likely that there will be many benefits from AI, however, as ever, it depends on how the technology is employed and the principles in use behind it.

The AI automation logic is leading organisations to think further about removing humans from interacting with customers and replacing them with robots. The difficulty with pursuing this approach is that customers are already frustrated at the lack of interaction they have with human beings in their service organisations. They lament on social media and crowd support sites that they cannot find a service organisation’s phone number to talk to someone. They complain that they must be a ‘VIP’ customer or a ‘Business’ customer to be able to speak to a human. When they do eventually find the phone number to talk to someone, customers are frustrated that they are held in queues with long waiting times (a tactic used to encourage them to use digital channels to self-serve) and complain that, while waiting in queues, they must endure repeated messages such as ‘We are experiencing long wait times. Did you know you can download our app or visit our website to [do what you want to do]?’ (another tactic used to encourage customers to self-serve).

Chatbots are just one particular example of AI that has caught the attention of leaders. Juniper Research reports: ‘Chatbots hold the potential one day to replace the tasks of many human workers with AI (Artificial Intelligence) programs sophisticated enough to hold fluent conversations with human users’.2 Juniper quoted appealing cost and time savings from using chatbots: ‘[A]verage time savings of just over 4 minutes per [chatbot] enquiry, equating to average cost savings in the range of $0.50–$0.70 per interaction’ when compared with traditional call centres.3

These kinds of numbers gain management’s attention. Saving four minutes per enquiry and equating that to cost savings is direct evidence of a Tayloristic approach still in use today.

Chatbots may seem appealing; however, is anyone thinking about the customer on the other end of these bots? Is anyone looking at the true systemic economics of these ‘savings’? Or are they focusing, as Taylor did, on unit productivity and unit cost? There are plenty of examples that show, once the bots are deployed, the anticipated savings on the bottom line don’t appear, leaving leaders confused as to why not.

In Australia, the government commissioned a computer program to recover debt, called the Online Compliance Intervention. The IT software was designed to check the income and benefits an employee was entitled to, matched what their employer had reported to the tax office. Prior to the implementation of this technology, a human being would do some investigation work and would follow up with people via letter and phone. This work was replaced by a robot that would do some checks and send out letters.

In a Media Release, The Minister for Human Services reported: ‘The new online compliance system, which became fully operational in July, is now initiating 20,000 compliance interventions a week – a jump from 20,000 a year previously. Over 3 years it is expected to carry out 1.7 million compliance interventions.’4

Sounds fantastic. The robot seems far more productive than the humans. However, thousands of recipients of debt recovery notices were later found to owe less or even nothing.5 ‘Robodebt’, as it has become known, is infamous for the great financial and emotional angst it caused many Australians, as well as incredible damage to the credibility of the Australian government. It led to a class action and resulted in a settlement worth $1.8bn between the commonwealth and victims of the scheme.6

Not all customers want to talk to a chatbot. When we worked in a large insurance company, we met the person who designed and implemented ‘conversational chatbot’ solutions, which aimed to provide ‘human-like’ conversational experiences for customers. Within the chatbot conversation flow was the option to automatically transfer the customer to a human being. This option was buried deep within the flow. When we asked why the option to speak to a human being wasn’t offered at the start of the conversation, the answer from the designer was that everyone would use it!

In their article titled, ‘Why your call center is only getting noisier’, McKinsey & Company highlights the issues that organisations face after deploying various technologies which were supposed to reduce costs and improve service but failed at both: ‘These technologies begin with websites, chat bots, and apps and extend to artificial- intelligence robots that simulate human conversations – redefining the way organizations interact with customers – as well as more tried-and-tested functionalities such as improved web, app, or self- service capabilities in interactive voice-response (IVR) systems. And yet, despite this plethora of technology solutions, we see that calls are not going away and instead are catching call-center executives off guard in their efforts to reduce volumes … in many instances, we’ve also observed that the volumes of unwanted calls exceed what would be expected during a learning period, or remain constant or rise over time, defeating strategic goals and leaving managers bewildered and unable to tie tech investments to improved operational outcomes.’7

For the foreseeable future, AI can only be a set of rules and algorithms. We don’t even fully understand how the human brain works yet, let alone create true artificial intelligence to try and replicate it. As reported in Wired – ‘Why Artificial Intelligence Is Not Like Your Brain – Yet’: ‘[T]hese systems have only a few million “neurons,” which are really just nodes with some input/ output connections. That’s puny compared to the 100 billion genuine neurons in your cranium. Read it and weep, Alexa! We’re talking 100 trillion synapses.’8

Senior leaders often espouse that they want their organisations to be innovative, continually improve, and be differentiated on service. However, once rules and algorithms are codified, and processes are locked into technology concrete, the ability to innovate and improve will be inhibited and sometimes nullified. If poor service design is robotised, quality of service will go down, customers will suffer, and costs will rise as failure demand pours in. So, while Taylor may have dreamt of replacing people with machines, the reality of doing so has been proven to be flawed in a service context.

This brings us to the third of the Taylorisms – Surveilling and monitoring employees.

MONITORING EMPLOYEES

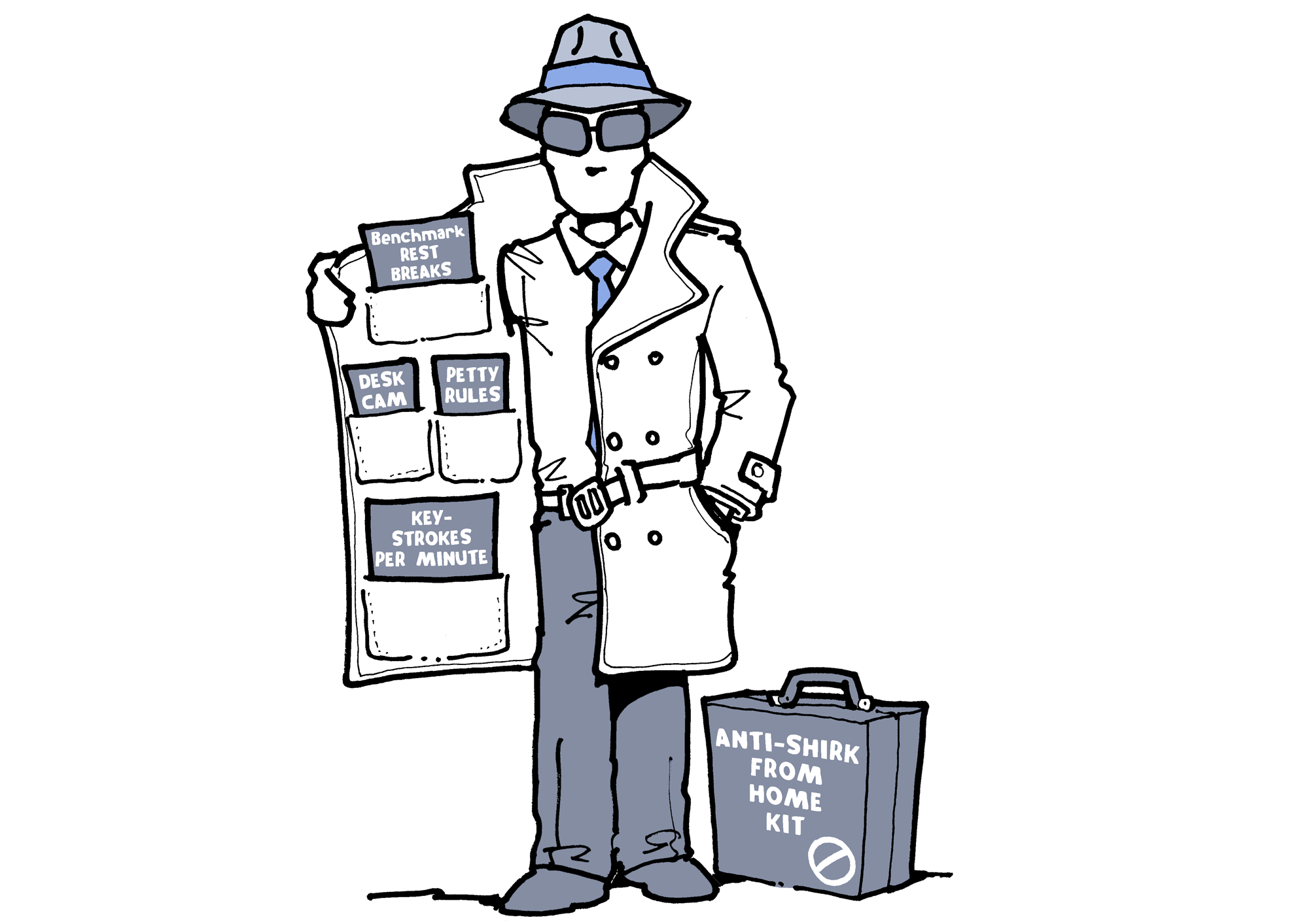

Taylor’s view of employees was that they were naturally lazy and shirkers. To ensure they did not shirk, and to increase productivity, he devised various methods to monitor their work and output. This often involved the technology of the time, for example, stopwatches, clipboards, and time-and-motion studies. Workers were monitored to ensure they met the standard times and received incentives for exceeding them.

In the Guardian article ‘Robots have already taken over our work, but they’re made of flesh and bone’, Brett Frischmann and Evan Selinger state: ‘The modern, digital version of Taylorism is more powerful than he could have ever imagined, and more dehumanising than his early critics could have predicted. Technological innovations have made it increasingly easy for managers to quickly and cheaply collect, process, evaluate and act upon massive amounts of information. … When the guiding assumption of management is that employees won’t be productive unless forced to be by constant observation, it engineers low morale and pushes people to act like resources that need to be micromanaged. Too often, we become what we’re expected to be.9

Surveilling and monitoring employees is on the increase – organisations are using sophisticated surveillance systems to monitor employees and make sure they are always productive. It is now common for technology to sit in the background, collecting data on what employees are doing. Technology tracks, for example, if employees are doing their work within the specified times; how many work items are in their queue, how long phone calls take, how much time is spent on non-work activity such as surfing the web or on social media, how many emails or instant messaging chats they send, and how much work they did that day. For field service workers, the technology tracks items such as how long they took to get to a job, how long they spent on a job, how long they spent on their breaks, and how many jobs they do per day. This data is collated and reviewed by managers and teams of specialists. The consequences for morale and attrition are dire.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic forced many employees to work from home, the situation has only worsened. As reported in the Guardian article ‘Shirking from home? Staff feel the heat as bosses ramp up remote surveillance’: ‘For many, one of the silver linings of lockdown was the shift to remote working: a chance to avoid the crushing commute, supermarket meal deals and an overbearing boss breathing down your neck. But as the Covid crisis continues, and more and more employers postpone or cancel plans for a return to the office, some managers are deploying increasing levels of surveillance in an attempt to recreate the oversight of the office at home.’10

The ABC reported in the article ‘Employee monitoring software surges as companies send staff home’: ‘For an increasing number of Australian workers, it is now the norm to have every movement tracked: what websites you visit; how long you spend on social media; how many keystrokes you do each minute and even when you go to the bathroom. Sales of software that monitors employees working remotely have surged since the coronavirus pandemic was declared, with some companies reporting a 300 per cent increase in customers in Australia.’11

In the Guardian article ‘Missing from desk: AI webcam raises remote surveillance concerns’: ‘[H]ome workers will have an AI-enabled webcam added to their computers that recognises their face, tags their location and scans for “breaches” of rules at random points during a shift. These include an “unknown person” detected at the desk via the facial recognition software, “missing from desk”, “detecting an idle user” and “unauthorised mobile phone usage”.’12

Personnel Today reported in the article ‘PwC facial recognition tool criticised for home working privacy invasion’ that ‘PwC has come under fire for the development of a facial recognition tool that logs when employees are absent from their computer screens while they work from home. The technology, which is being developed specifically for financial institutions, recognises the faces of workers via their computer’s webcam and requires them to provide a written reason for any absences, including toilet breaks.’13

COVID-19 has led to what’s being dubbed The Great Resignation.14 In research conducted by Microsoft, the article ‘The Next Great Disruption Is Hybrid Work—Are We Ready?’ reported that ‘over 40 percent of the global workforce [are] considering leaving their employer’.15 “The movement of talent is so significant and so sharp that it’s different to probably anything we’ve seen in living memory,” behavioural scientist Aaron McEwan, from global research and advisory firm Gartner, told ABC RN’s This Working Life. “Today, employees don’t want to be seen as workers. They want to be seen as complex human beings with rich, full lives,” Mr McEwan said.16

Taylor’s view was wrong. People aren’t naturally lazy or shirkers. They don’t need to be surveilled and monitored. If leaders continue down the path set by Taylor, then the inevitable result will be more people joining The Great Resignation.

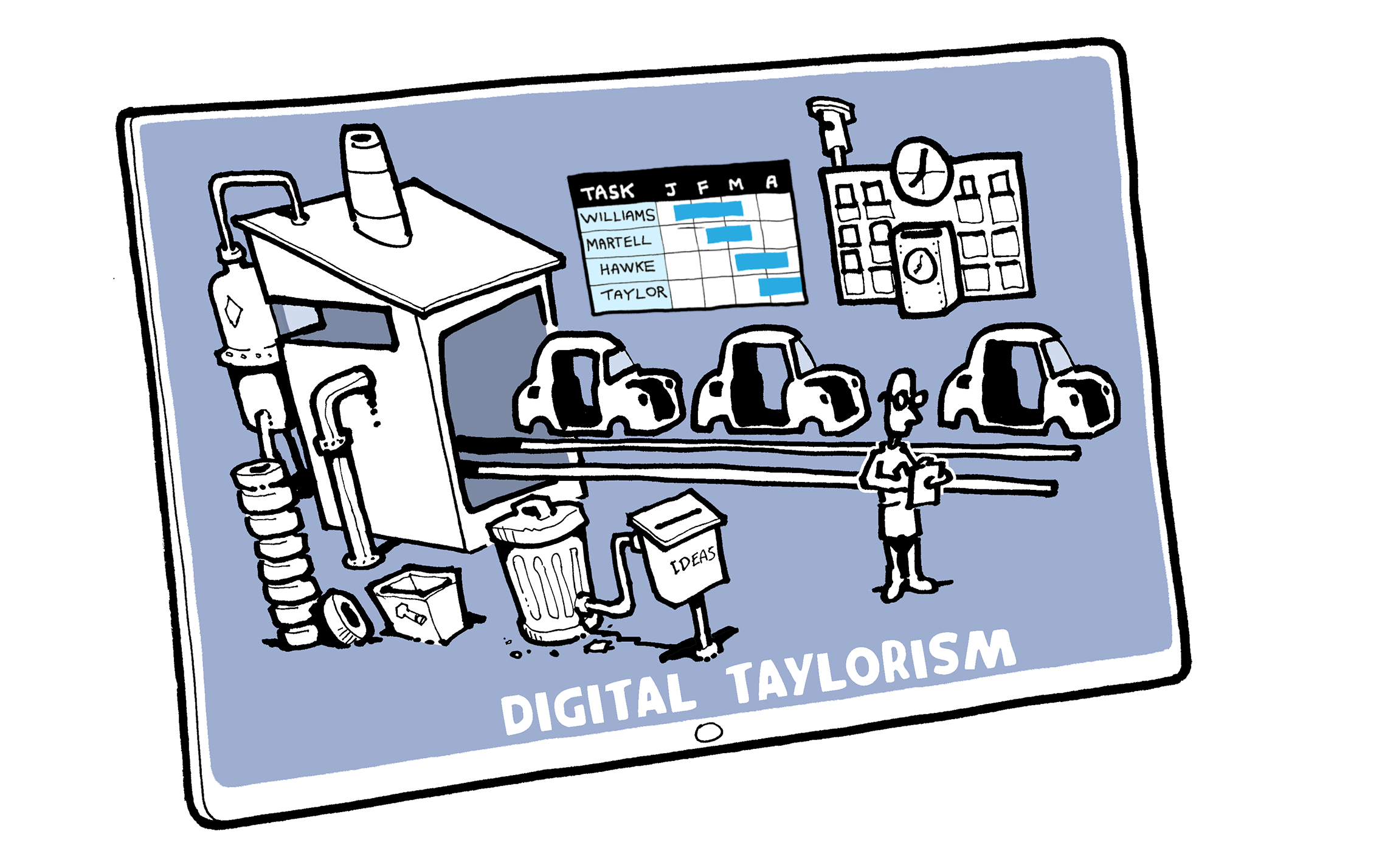

DIGITAL TAYLORISM

In recent times a new term has entered the English lexicon: digital Taylorism. This term is the modern version of Taylorism. It takes Taylor’s concepts to new levels through the use of technology, as we’ve explored in the three preceding sections.

The New York Times published an article about Amazon, with the headline ‘Inside Amazon: Wrestling Big Ideas in a Bruising Workplace’: ‘In Amazon warehouses, employees are monitored by sophisticated electronic systems to ensure they are packing enough boxes every hour … in its offices, Amazon uses a self-reinforcing set of management, data and psychological tools to spur its tens of thousands of white-collar employees to do more and more.’17

The Economist featured a piece on the article claiming that it had struck a chord with workers across a range of different organisations: ‘[T]he article attracted more than 5,800 online comments, a record for a Times article, and a remarkable number of commenters claimed that their employers had adopted similar policies … digital Taylorism looks set to be a more powerful force than its analogue predecessor. The prominent technology firms that set the tone for much of the business world are embracing it. … The onward march of technology is producing ever more sophisticated ways of measuring and monitoring human resources.’18

Over 100 years after their inception, the legacies of Taylorism are not only still in use but are flourishing.

PEOPLE ARE NOT MACHINES

Taylor operated on a misguided assumption that people can be treated as machines. But an organisation that treats its people like machines, by obsessively managing people’s activity and constraining people with rules and regulations that contradict common sense and a sense of fairness, will inhibit its ability to meet the purpose the organisation has been set up to accomplish.

It can easily be experienced as hypocritical when the leadership extols vision and mission statements about the apparent value of people, customers, and being the chosen supplier/employer when, at the same time, people are treated as objects.

People have an advantage over machines: they take into account purpose, and they can adapt and change in furtherance of that purpose as conditions change. The distinction between people and object relations may seem very simple and obvious. However, despite this simplicity, we all sometimes muddle them up. We have heard leaders describe people as units (of labour), resources, or numbers. Treating people in this way may not even be deliberate, but it has the effect of objectification. It can be comforting for the leadership to assume the people–object relationship because it gives the illusion that people can be controlled. We can control objects; we can only influence people. Treating people as objects breeds cynicism and malicious compliance.

The irony is that attempts to control people completely are essentially self-defeating. Not only is there a question of morality but the energy required to maintain such a controlling regime will not, over time, produce an efficient outcome since, by definition, it stifles initiative, creativity, and enthusiasm. The energy put into control will exceed the energy produced from the ‘controlled’ person or group.

Research undertaken by SEEK has concluded that employees want to work in organisations where they will be engaged in their work; relationships are cultivated, supported, and valued; their work has meaning and purpose, and results in a sense of achievement; their personal goals are supported with a clear career direction; there is a culture of trust and flexible work models; and they can learn new skills to further their career.19

Digital Taylorism – treating people as machines or objects to be controlled – is the complete opposite of what employees are looking for. The importance of the employee’s perspective is gaining in relevance too, with increasing skill shortages and competing demand for talented workers. SEEK reports: ‘As Australia continues to grapple with COVID-19, employers across key industries are experiencing a new level of demand for workers. The competition for talent in these areas can be tough.’20

The impact of these factors for organisations is that if they are to have successful futures, they need to leave Taylorism behind and focus on creating attractive, productive, and positively viewed places to work. The starting point is to understand not only what ‘the organisation’ needs but also what people need, and what they assess as worthy or unworthy. Only then can leaders be really effective in introducing change and begin building a positively viewed organisation that brings people together to productively achieve the purpose the organisation has been set up to accomplish.

This article contains excerpts from Chapter 1 of our latest book Reconceive: New thinking for progressive leaders to create productive, positively viewed service organisations

SUBSCRIBE FOR LATEST ARTICLES

If you’d like to read our latest articles then we can send them to you each time they are published. Please subscribe below.

The Puritan Gift: triumph, collapse and revival or an American Dream, Kenneth Hopper and William Hopper, I. B. Tauris, 2007 ↩

Chatbot Conversations to deliver $8 billion in Cost savings by 2022, Juniper ↩

Chatbots, A game changer for banking & healthcare, saving $8 billion annually by 2022, Juniper Research, 9 May 2017. ↩

New technology helps raise $4.5 million in welfare debts a day, The Hon Alan Tudge MP, #NotMyDebt, 5 Dec 2016. ↩

Centrelink’s ‘deeply flawed’ robo-debt to face new investigation, The Guardian, Australian Associated Press, 13 Jun 2018. ↩

Robodebt: court approves $1.8bn settlement for victims of government’s ‘shameful’ failure, The Guardian, Luke Henriques-Gomes, 11 Jun 2021. ↩

Why your call center is only getting noisier, Maurice Hage Obeid, Kevin Neher, and Greg Phalin, McKinsey & Company Marketing & Sales, Our Insights, July 2017. ↩

Why Artificial Intelligence Is Not Like Your Brain – Yet, Lee Simmons, Wired, 3 Jan 2018. ↩

Robots have already taken over our work, but they’re made of flesh and bone, Brett Frischmann and Evan Selinger, The Guardian, 25 Sep 2017. ↩

Shirking from home? Staff feel the heat as bosses ramp up remote surveillance, The Guardian, Alex Hern, 27 Sep 2020. ↩

Employee monitoring software surges as companies send staff home, ABC News, Patrick Wood, 21 May 2020. ↩

”Missing from desk”: AI webcam raises remote surveillance concerns, The Guardian, Peter Walker, 27 Mar 2021. ↩

PwC facial recognition tool criticised for home working privacy invasion, Personnel Today, Ashleigh Webber, 16 Jun 2020. ↩

Buckle up, The Great Resignation is heading Australia’s way, This Working Life with Lisa Leong, ABC Radio National, 13 Sep 2021. ↩

The Next Great Disruption Is Hybrid Work—Are We Ready?, The Work Trend Index, Microsoft, 22 Mar 2021. ↩

Here comes the Great Resignation. Why millions of employees could quit their jobs post-pandemic, ABC Radio National, Lisa Leong with Monique Ross for This Working Life, 23 Sep 2021. ↩

Inside Amazon: Wrestling Big Ideas in a Bruising Workplace, Jodi Kantor and David Streitfeld, The New York Times, 15 Aug 2015. ↩

Digital Taylorism, Schumpeter, The Economist, 10 Sep 2015. ↩

9 things employees expect in a workplace in 2021, Helen Tobler, SEEK Employer ↩

Australia’s top 20 most-needed workers, SEEK Employment Trends, Susan Muldowney ↩