In the Financial Times, Sarah O’Connor warned: ‘In the pursuit of efficiency, [call centres] have ground humanity out of their workers — the very quality they now want to get back … If the problem is that emotionally exhausted workers are giving a bad experience to customers, then a simpler solution would be to prevent them from getting so burnt out in the first place.’1

The results of this type of failed improvement approach for customers was accurately described by fellow columnist Camilla Cavendish in her article ‘Press 1 for hell’: ‘“Due to coronavirus, it will take longer to answer your call.” Who, exactly, are they kidding? A year into the crisis, some of the biggest institutions are still blaming Covid-19 for their monstrous incompetence and callow indifference. All those hours saved on the commute by working from home are now being wasted in the vortex of banks, energy and phone companies’ customer services whose idea of accountability is chatbots.’2

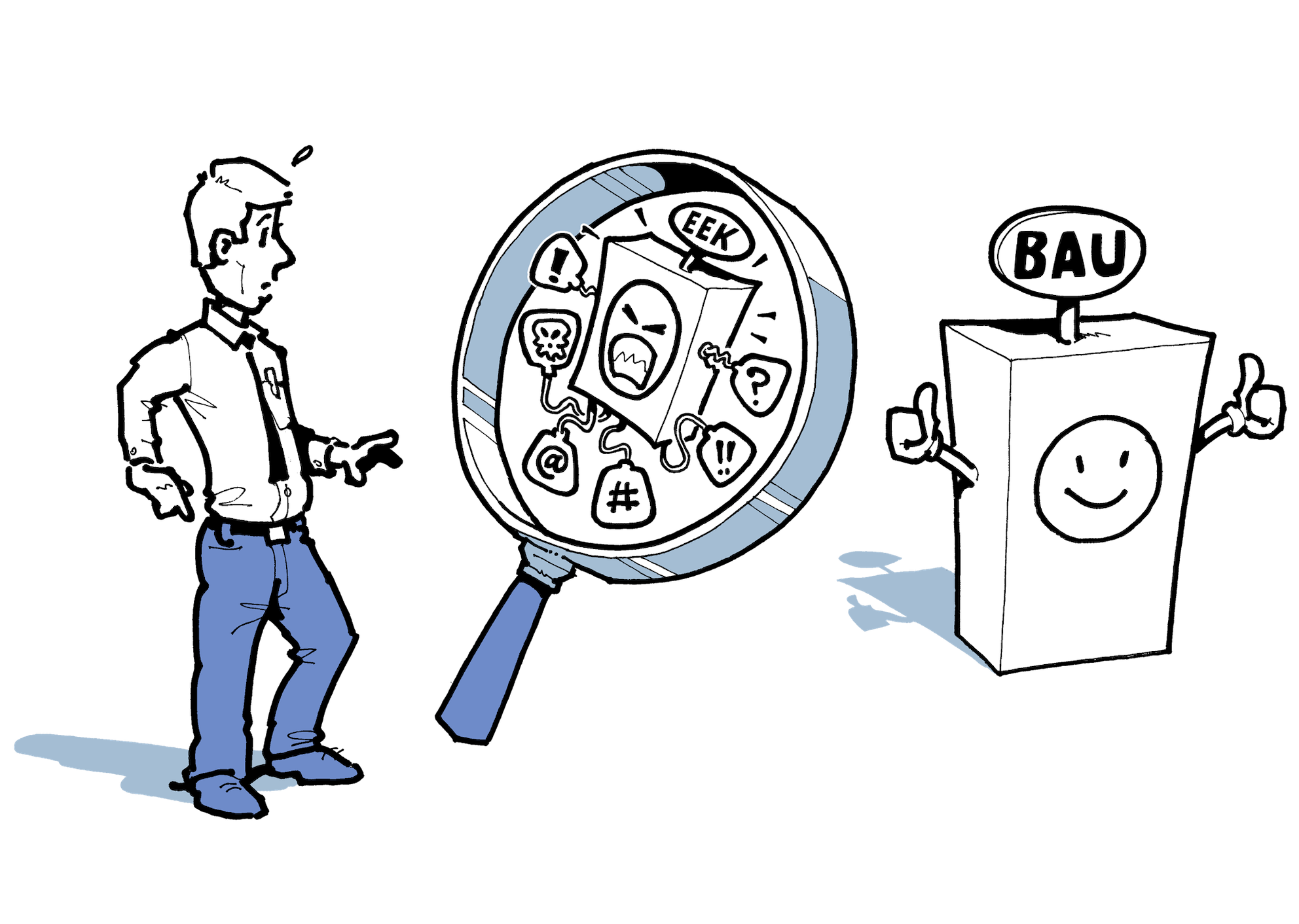

The service quality improvement and cost minimisation efforts described by O’Connor and Cavendish are indeed destined to fail. The reason for the futility of these approaches was identified over 30 years ago by John Seddon, the British occupational psychologist. He analysed the reasons why people contacted public and private sector organisations and found that routinely up to 80 per cent of the contacts made were avoidable. Seddon termed these unnecessary contacts ‘failure demand’.

Failure demand is caused by failures to do something, or do something correctly, for the customer. It lurks everywhere a customer interacts with an organisation; for example, in the contact centre, retail store, field services, or digital channel. Because of failure demand, each channel frequently becomes a rework centre, patching up the results of faulty internal organisational systems and structures.

Organisations have unwittingly become very good at turning a customer demand into a failure demand. If that’s not frustrating enough for customers, many organisations inadvertently generate failure demand. The following are two clear examples of how easy this is to achieve.

Case 1: A telecommunications organisation sent out letters to advise their customers that certain legacy services would be turned off. Many of the customers they mailed didn’t even use those services, so these customers flooded the contact centre to ask, ‘Does this apply to me?’

Case 2: A financial service organisation sent out computer- generated letters to their customers explaining there had been a change in the law and how it might affect their investments. The change only affected a small number of customers; however, it had been sent out to all customers ‘just in case people were missed’. The organisation was flooded with enquiries from customers for whom the advice was irrelevant, which took them months to clear.

Both are clear cases of the organisations generating their own failure demand. Both are also clear examples of how service improvement programs are unaware of the hidden expense of failure demand.

Another example is when call centre contracts focus on cost per call, minimising call duration and fast pick-up times. But if, typically, 20 per cent, and as much as 80 per cent, of calls are unnecessary in the first place, handling them cheaper or faster makes marginal sense. Calls prompted by delivery problems, incorrect websites, confusing packaging, baffling instructions, incomprehensible forms, misunderstood advertising, or other internal organisational failures are simply repeat work. Empathy training programs are not the tool for this. The failures need to be stopped at their source.

Failure demand is such a simple concept, and understanding it and acting on it is one of the single greatest levers leaders have to improve digital and service delivery, increase capacity, and reduce operational expense. However, until leaders learn to see failure demand and, more importantly, permanently eliminate it once the root cause is identified and fixed, it remains an invisible problem.

REMOVING FAILURE DEMAND

Removing failure demand represents one of the greatest opportunities to improve service, increase capacity, and reduce operational expense in your business. Ignoring the nature of customer demand is to ignore one of the greatest levers you have to improve performance.

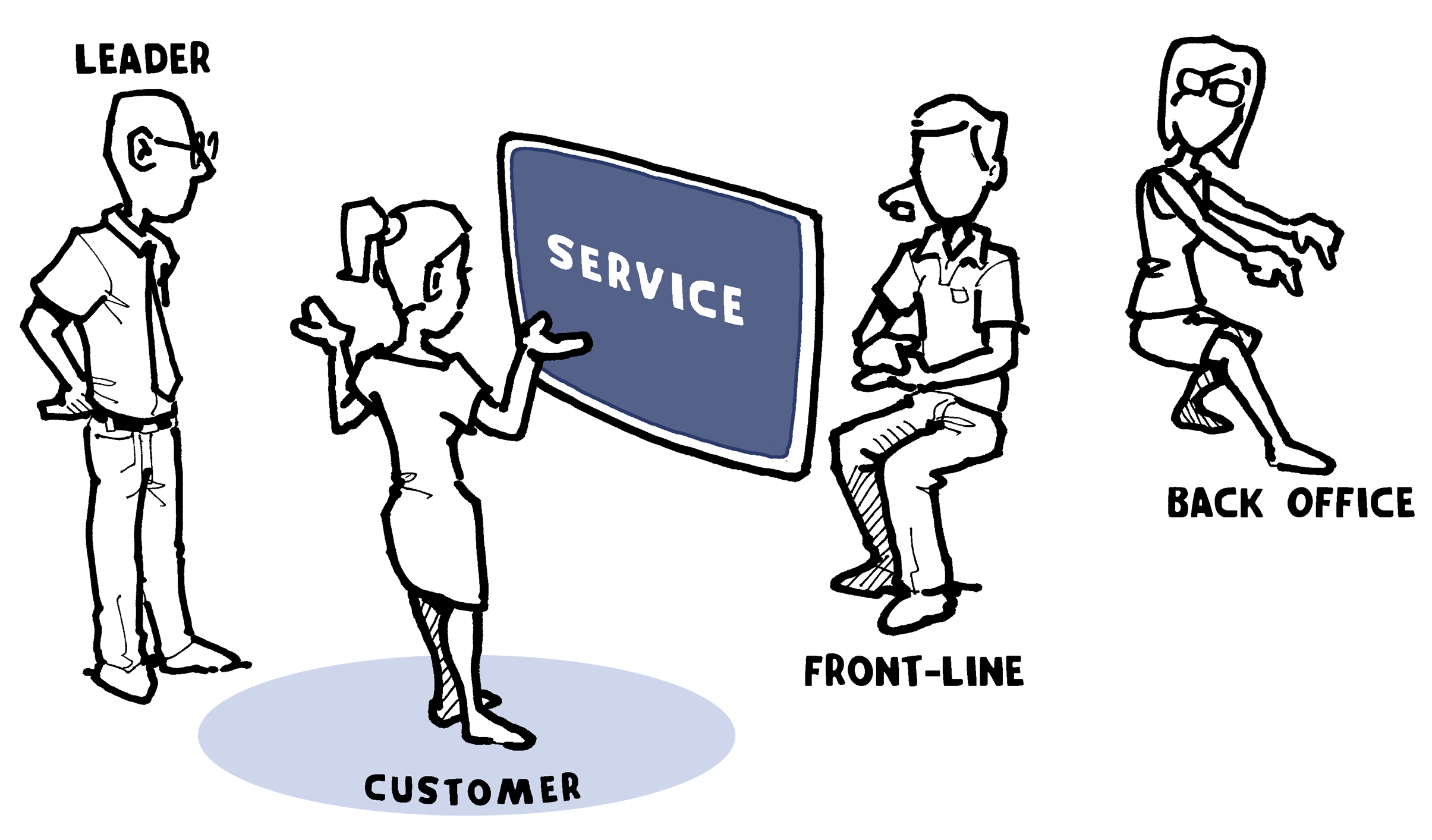

What is really required is the application of a different approach, where what creates value for customers and how best to service them sets the context for improvement, where people are organised and enabled to do that work more effectively, and where productive leadership practices are embedded. Then, technology needs to be quickly applied which complements the more effective operating model, which provides further value and further reduction in cost. This unique approach enables leaders to achieve the outcomes they are looking for in months, not years.

Why isn’t everyone already doing this? Because it requires that the conventional assumptions and beliefs that shape behaviour about digital and service delivery, leadership, and culture be questioned and challenged.

To understand and challenge one’s own assumptions, a leader needs to take a customer’s perspective and spend time seeing for themselves what happens in their front-line (and back-office) operations. Senior executives are astonished when they realise the money wasted and damage inadvertently inflicted on their customers, employees, and brand. The good news is that they also quickly see the opportunity for improvement: stunning cost reductions and exceptional service delivery improvements are made visible.

An example of where this approach was adopted and the benefits realised is provided by Renato Mota, Chief Executive Officer of Insignia Financial. He recounts the experience at Insignia Financial when he and his leadership team understood and challenged their assumptions by taking a customer’s perspective and spent time seeing for themselves what happened in the front-line:

We went through a process of reframing. The process of reframing took us to a point that we realised going back is not an option. There reaches a point where you actually can’t go back. Once your thinking changes, even a little bit, there’s a point of no return.

What does that look like? Taking very senior managers in the organisation into the call centre and listening to calls, understanding what is value.

A good example of understanding value: you’d be on a call, you’d be listening to one of the calls, the client calls in and says, ‘I want to reset my password’. The call centre operator helps them reset their password and asks, ‘Is there anything else you need to do?’, the customer replies, ‘No, that’s all good, thanks’, and hangs up.

We then go on to analyse that. Was that value? Did we create value? The first response is, ‘Well, yeah, they wanted their password reset,’ but I’m yet to meet someone who wakes up in the morning and wants their password reset. Fundamentally, they were trying to log on to do something – the reality is we didn’t know what they were trying to do. We had no idea. That is just a small example. There were thousands of these examples every day.

The senior management team went through a process of resetting their minds around what value was and how much demand, both failure and value demand, was coming through our touchpoints. And we started with our call centre. I can tell you there was a tremendous amount of failure demand, either resetting passwords, following up transactions, following up communications we’ve sent to them that they didn’t understand – these were all sources of failure demand; demands that were being put on our system, at our expense, in a lot of times that we had created.

So, we learned we had a problem, a significant problem. Now, [it was] a problem in a relative sense; the business was performing well, but in the organisation, we were creating false demands, or failure demands, into our own organisation, and once you look at that through a different lens, you can’t look at that and ignore it. We knew we had a problem.

How do you deal with the problem? Well, you’ve got to unpack those myths, unpack those assumptions. Whether we like to accept it or not, we are all full of assumptions, assumptions that SLAs and KPIs are going to lead to more efficient businesses. Assumptions around, well, surely if someone’s on the phone for 10 minutes, rather than 2 minutes, that means the costs of running our business is going to be more expensive; this has got to be more expensive. There were a whole bunch of assumptions that we had to go through, reframing our own mindset. We couldn’t say no to the opportunity once we had seen it with our own eyes.

The question remains: Are you ignoring one of the greatest levers you have for improving performance in your organisation?

This article contains excerpts from Chapter 11 of our latest book Reconceive: New thinking for progressive leaders to create productive, positively viewed service organisations

SUBSCRIBE FOR LATEST ARTICLES

If you’d like to read our latest articles then we can send them to you each time they are published. Please subscribe below.

Portions of this article were first written by Dr Peter Middleton in a letter to the Financial Times